What is AES?

AES, or the Advanced Encryption Standard, is a encryption standard established by the National Institute of Standards (NIST).

Rijndael is the specific algorithm used in AES. It is a symmetrical block cipher, meaning that it operates on blocks of data and can encrypt and decrypt data using only one key (as opposed to asymmetrical encryption, which needs a public and a private key).

Brief History

AES was created in 1997 through a competition created by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which wanted to replace the Data Encryption Standard (DES).

DES was already proven to be insecure, and NIST needed a new algorithm that was “an unclassified, publicly disclosed encryption algorithm capable of protecting sensitive government information well into the next century”. Several groups submitted algorithms to the competition. Submitted ciphers were evaluated by the NSA for speed, security, and feasibility on low powered devices (smart cards, etc.).

Eventually, an algorithm submitted by Belgian cryptographers Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen, called Rijndael (a combination of their last names) was selected. Specifically, three variants with different key sizes, 128-bit, 192-bit, and 256-bit, were chosen. Eventually, it would become U.S. FIPS PUB 197.

In 2003, the US government officially announced that AES could be used to protect confidential information, and was used by the NSA to encrypt important documents.

Today, AES is one of the most popular block ciphers in existence due to it’s high performance and security it provides. AES is implemented in nearly every language, and hardware acceleration is available on most processors. On x86, acceleration is provided by the AES-NI instruction set.

AES is currently unbroken, with the only possible attacks based on attacking side-channel implementations. This means that the only attacks that work are on the implementation of AES such as hardware glitches and timing attacks. Otherwise, brute forcing AES would take more time then the current age of the universe.

AES implementation

AES uses four basic operations, grouped in rounds. The number of rounds depends on the AES bit size. The higher bit size, the more rounds.

Since I implemented AES-128 in Google Sheets, that is what we will be looking at specifically.

For AES-128, there are 10 rounds, plus an initial round that only has the AddRoundKey step. The final round does not have a MixColumns step.

Below is a diagram of a round for both encryption and decryption.

AES-128 requires a key with a size of 128-bits (16 bytes) and a plaintext with a size of 128-bits (16 bytes). This is because AES is a block cipher, not a stream cipher. A stream cipher can operate on data of variable size, while block ciphers can only operate of blocks of data. Because AES is a block cipher, the data MUST be padded to a length of 16 bytes.

AES-128 also has different operating modes: CBC, ECB, CTR, OCB, and CFB. The only mode we care about is ECB, or Electronic Code Book, because it is one of the easiest methods to implement. Other AES-128 operating modes require an IV (initialization vector), which increases the complexity of encrypting and decrypting.

Byte organization

The bytes in the plaintext and key are arranged in a 4x4 matrix, top to bottom, left to right. For example, 00112233445566778899AABBCCDDEEFF becomes

00 44 88 CC

11 55 99 DD

22 66 AA EE

33 77 BB FF

Important stuff to know

sbox and inverse sbox

A sbox is a table that takes an input value, looks it up, and outputs another value. The the inverse sbox takes the output from the sbox, and restores it to the original input value.

The sbox hides relationships between the key and the output data and makes linear analysis much harder to do.

The sbox isn’t actually random. It was constructed using a formula designed to avoid pairing certain values to other values, so that analysis would be much harder.

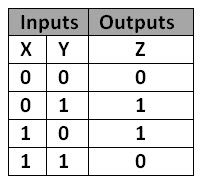

XOR

A basic operation that operates on the binary level. It is only true if and only if one of the bits is 1.

XOR is really important in cryptography because XOR is an easily reversible operation. Let’s say we have a number: 0xDE. Now, let’s pretend that 0xAD is my encryption key. If I XOR 0xDE by 0xAD, I get 0x73. 0x73 is my ciphertext. Now, if I XOR that by the key (0xAD) again, I get 0xDE, which is my original number. Interestingly, if I XOR 0x73 by 0xDE, I get 0xAD, which is what I XORed 0xDE by.

Galois / Finite Field

In simple terms, a Finite Field is a matrix that has a maximum limit before values wrap around. Finite fields are defined by the equation p^k, where p is a prime and k is a positive integer. p is the characteristic of the finite field, because adding p copies of any number is equal to 0.

A Galois Field is a finite field with characteristic 2. Galois Fields can be identified with the notation GF(x), where x is equal to 2^k.

There are only two operations in a finite field: addition and multiplication.

Addition is defined as “adding two of these polynomials together, and reducing the result modulo the characteristic.” In AES, the Galois field is defined as GF(256), or 2^8.

When the characteristic is 2, addition is simply just XORing the the values together.

Multiplication in a finite field is much more complicated. First, multiply the numbers normally, such as in algebra. Then, divide that (because it won’t fit into an 8 bit field) by a fixed number, known as an irreducible polynomial.

x8 + x4 + x3 + x + 1 = 0x11B

We then divide the product of the two input numbers by this polynomial, and the remainder of the division is our product.

In Javascript:

/*

* Multiply two values in a Galois Field of size 2^8

* @param {Number} a - A hexadecimal number to multiply

* @param {Number} b - A hexadecimal number to multiply a by

* @returns {Number} - Result of multiplying a and b in a Galois field

*/

function GMUL(a, b) {

// Convert hex strings into decimal numbers

var a = parseInt(a, 16);

var b = parseInt(b, 16);

var v = new Number;

v = 0;

while (b != 0){

if (b & 1)

v ^= a;

b >>= 1;

if (a & (1 << (8 - 1))){

a <<= 1;

a ^= 0x11B;

} else {

a <<= 1;

}

}

// Convert number back to hex, uppercase, and pad with zeros

return pad(v.toString(16).toUpperCase(), 2);

}

rcon

The rcon, or round constant, is a constant number that is different for each round. It is simply defined as 2^n, where n is the round number. This is important for generating the key schedule, which is explained next.

Key Schedule

Each round of AES uses a different key. Each key is derived from the previous key, and so the key schedule changes based on the input key.

For AES-128, we need to expand a 128-bit key to 11 different 128-bit keys

The first key is always the input key.

To generate the rest of the keys, follow the steps:

1. For the first column of the new key, take the last column of the previous key and rotate by moving everything up by one.

2. Use the sbox to substitute the bytes

3. XOR that by the first column and the round constant

4. For the second column, take the new first column and XOR it with the second column of the previous key.

5. For the third column, take the new second column and XOR it with the third column of the previous key.

6. For the last column, take the new third column and XOR it with the last column of the previous key.

Operations

SubBytes

SubBytes is one of the most simple operations. Here, we simply replace each byte with the corresponding value in the sbox.

For example:

00 71 07 16

11 73 11 0B

07 61 76 72

70 04 79 00

becomes

63 A3 C5 47

82 8F 82 2B

C5 EF 38 40

51 F2 B6 63

ShiftRows

ShiftRows is another easy operations. The rows in the matrix each shift by a predetermined amount. This is also known as a rotation. Bytes that “fall off” one end are inserted at the other end.

In AES, the first row is left unchanged. The second row is shifted by one byte to the left. The third row is shifted by two bytes to the left, and the fourth row is shifted by three bytes.

This step is an example of a transposition cipher, which merely moves around bytes instead of modifying them.

MixColumns

MixColumns is a very important, yet hard step to calculate. This is where knowledge of the Galois Field and general matrix multiplication is necessary.

The Rijndael Galois Field is defined as:

The MixColumns step operates on one column at a time (as the name suggests). b is the output column, and a is the corresponding columns in the input matrix.

To calculate a value in this step, use the standard matrix multiplication rules and multiply Rijndael’s Galois Field with the input “column”, except that multiplication still follows the rules of multiplication in a finite field.

Or, to put it another way:

b0 is the result of the MixColumns operation, and a0 is the corresponding cell of the input.

AddRoundKey

This step combines the round key with the current data (or state) using an XOR operation.

Decryption

In general, to decrypt, we do the inverse of each operation.

SubBytes

Instead of substituting bytes in the sbox, we use the inverse sbox to replace bytes.

ShiftRows

We reverse the direction of the rotation, so instead of rotating left, we rotate right. However, the rotation length remains the same.

MixColumns

Same operations as before, except we multiply using a different Galois Field.

This will restore each value back to the original.

AddRoundKey

AddRoundKey remains the same (XOR property, remember).

Implementation in Google Sheets/Excel

For this, there were two main concerns: speed and accuracy. I will not go over every single detail, but instead go over some of the optimizations and quirks I had to deal with.

Useful stuff

- HEX2DEC - Converts a decimal number to a hex string

- DEC2HEX - Converts a hexadecimal string to a number

- The & operator - It concats two strings together. For example, “A” & “B” becomes “AB”

- CONCATENATE - Concatenates any number of strings together

- CHAR - Convert a number into a character

- CODE - Convert a character into a number

Fast XOR

There are two ways to do XOR in Google Sheets.

The first method is using a Google Script:

/*

* XOR two numbers

* @param {Number} a - A hexadecimal number to XOR

* @param {Number} b - A hexadecimal number to XOR

* @returns {Number} - Hexadecimal result of XORing a and b

*/

function XOR(a, b) {

return (parseInt(a, 16) ^ parseInt(b, 16)).toString(16);

}

This function is incredibly simple. Ignoring the conversion functions, we get

function XOR(a, b) {

return a ^ b;

}

^ is the XOR operator in Javascript, which is what Google Scripts uses.

To use this in Google Sheets, all I have to do is do =XOR(A1, B1), where A1 and B1 are the cells containing the hexadecimal values I want to XOR.

Total runtime after generating a new key or message (meaning a full recalculation) is almost 30 minutes. This is because it takes for Google Scripts to “prepare to run”, and only a certain amount of parallel executions can occur. Also, Google Sheets attempts to calculate all the values all at once, but has to recalculate again after the first couple things finish. It’s pretty bad at figuring out what cells depend on what cells :(

Therefore, we need a faster XOR method. We can take advantage of a property of XORing two one byte hexadecimal values.

Let’s say we have two numbers: 0xAB and 0xCD. Convert this into binary: 10101011 and 11001101. When we XOR this, we’re actually XORing each bit individually. The other bits in the number don’t really matter.

A property of expressing a byte as a hexadecimal is that each digit corresponds to four bits. The first digit is the first four bits, and the last digit is the last four bits. Therefore, A is 1010, B is 1011, C is 1100, and D is 1101. We can XOR A and C, then XOR B and D. We then cat the two results together.

A visual example:

0xAB ^ 0xCD

10101011 ^ 11001101

CONCAT(1010 ^ 1100, 1011 ^ 1101)

Since we are now XORing two one digit numbers, there are a total of 256 different XOR input values (16^2). This makes it incredibly easy to do a lookup table.

An excerpt:

Input XOR

00 0

01 1

02 2

03 3

04 4

05 5

06 6

07 7

08 8

09 9

0A A

0B B

0C C

0D D

0E E

0F F

10 1

11 0

...

So, when we want to XOR two numbers, we first look up the left two digits, then the right to digits.

Example: 0xAB and 0xCD. First, we lookup what is A and C XORed. In the table, we find AC is 6. Then, we lookup what B and D is XORed, which is 6. Then, we concat those together to get 66. Therefore, 0xAB ^ 0xCD is 0x66.

Implemented in Google Sheets:

=VLOOKUP(LEFT(R19)&LEFT(F19),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(R19)&RIGHT(F19),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)

where AESXORTable is a named range for the XOR lookup table.

SubBytes

To do replace bytes using a sbox, we use VLOOKUP. sbox and inverse sbox is stored in the spreadsheet like this:

Input sbox Inverse sbox

00 63 52

01 7C 09

02 77 6A

03 7B D5

04 F2 30

05 6B 36

06 6F A5

07 C5 38

08 30 BF

To lookup a value, we use VLOOKUP with the input value as the key. If I was looking for an sbox value, I would do:

=VLOOKUP(V15,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$2:$B$257,2, TRUE)

If I wanted to look for an inverse sbox value:

=VLOOKUP(V15,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$2:$B$257, 3, TRUE)

Notice that I changed the column number from 2 to 3.

ShiftRows

This is incredibly easy to do in spreadsheets. All you have to do is set one cell to another cell.

=A15

To do the shift, instead of setting it equal to the cell 4 columns to the left, set it to 4 - (shift).

=A1 =A2 =A3 =A4

=B2 =B3 =B4 =B1

=C3 =C4 =C1 =C2

=C4 =C1 =C2 =C3

MixColumns

MixColumns is implemented in Google Sheets using a lookup table. Generally speaking, in Google Sheets, it’s faster to use builtin functions rather than using a script, because scripts take a while to run.

Since the MixColumns step only multiplies by 02, 03, 09, 0B, 0D, and 0E, we can build a lookup table. Total, there are 16^2 * 6 values in the lookup table, or 1,536 values. The table is organized with the input value as the index, the number to multiply as the column identifier, and the intersection of those is the result of a multiplication.

An excerpt is below:

Input 2 3 09 0B 0D 0E

00 00 00 00 00 00 00

01 02 03 09 0B 0D 0E

02 04 06 12 16 1A 1C

03 06 05 1B 1D 17 12

04 08 0C 24 2C 34 38

05 0A 0F 2D 27 39 36

06 0C 0A 36 3A 2E 24

07 0E 09 3F 31 23 2A

08 10 18 48 58 68 70

09 12 1B 41 53 65 7E

If I wanted to multiply 01 by 09, I would find 01 on the left most column, then find the corresponding value in the 09 column. Thus, the answer would by 09.

The formula used for each cell in the MixColumns step is as follows:

=VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))&LEFT(VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))&RIGHT(VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE))&LEFT(VLOOKUP(LEFT(N25)&LEFT(N26),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(N25)&RIGHT(N26),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))&LEFT(VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))&RIGHT(VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE))&RIGHT(VLOOKUP(LEFT(N25)&LEFT(N26),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(N25)&RIGHT(N26),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)

It looks really long, but most of it is overhead from the fast XOR method.

Breaking it down:

1. We first find the results of the multiplication using VLOOKUP (VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))

2. We then XOR it using our fast XOR method (VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))&LEFT(VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE))&RIGHT(VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE))

3. We then XOR it with the other parts, because that’s how addition in a Galois Field works.

Converting this into using the XOR formula:

=XOR(XOR(XOR(VLOOKUP(N23,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,4,TRUE), VLOOKUP(N24,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$1:$E$257,5,TRUE)),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)), N25), N26)

Much easier :)

AddRoundKey

We use the fast XOR method to XOR the round key with the current state.

=VLOOKUP(LEFT(F9)&LEFT(F15),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(F9)&RIGHT(F15),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)

rcon

Although we could hardcode the rcon values, where’s the fun in that?

=VLOOKUP(RIGHT(C19,1),'AES-128 Tables'!$K$2:$L$12,2,FALSE)

C19 is a cell containing the text “Round 1”. RIGHT(C19, 1) extracts the right most number, which is the round number. It then looks up the value in a lookup table to get the rcon value.

Key Schedule / Key Expansion

The formula for key expansion differs between columns. Below is the formula for the first column:

=VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(I16,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$2:$B$257,2,TRUE))&LEFT(F15),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(I16,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$2:$B$257,2,TRUE))&RIGHT(F15),AESXORTable,2,FALSE))&LEFT($Z$19),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(LEFT(VLOOKUP(I16,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$2:$B$257,2,TRUE))&LEFT(F15),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(VLOOKUP(I16,'AES-128 Tables'!$A$2:$B$257,2,TRUE))&RIGHT(F15),AESXORTable,2,FALSE))&RIGHT($Z$19),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)

We have to work from the inside to outside. At the top level, it XORs two numbers. The first number is the result of XORing two numbers as defined above, when I explained the key expansion step. The second number is the round constant.

So, although it looks really complicated, most of it is just XOR overhead. If I were to use the XOR formula:

=XOR(XOR(I16, F15), $Z$19)

The formula for the rest of the columns are much easer.

=VLOOKUP(LEFT(F20)&LEFT(G16),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)&VLOOKUP(RIGHT(F20)&RIGHT(G16),AESXORTable,2,FALSE)

Using the XOR formula:

XOR(F20, G16)

Resources

Below are links to some websites I found useful: